In Conversation with Stan Allen

RM1000: Professor Allen we are humbled and extremely grateful for your time today. You have been a seminal figure in architectural education for over three decades; your impact on students, theoretical discourse and the profession are vast and powerful.

Stan Allen: I’m always happy to talk to students. It’s what I do.

RM1000: We wanted to start by asking if you could talk about section and notation and the roles they play in grounding the practice and making of architecture?

SA: Notational practices enter architecture largely in relationship to questions of program, and mainly around issues of time as opposed to spatial issues. Section, even in the origin of the word, implies a cut through time, a freezing of time, whereas notation tends to relate to phenomena that unfold in time. Historically, the two architects I associate with notation are Bernard Tschumi and Rem Koolhaas, and it’s not accidental that both Tschumi and Koolhaas foreground issues of program. I think there is an important distinction to be made between the architectural plan and mapping practices. Mapping practices tend to be analytical, that is to say, after the fact. You map existing conditions. The plan, for me, always has a projective component; it anticipates a future condition rather than records what exists. Notation is at work in both plans and maps, but I think it has a more assertive presence in mapping practices.

“Mapping practices tend to be analytical, that is to say after the fact. You map existing conditions. The plan, for me, always has a projective component; it anticipates a future condition rather than records what exists.”

RM1000: As you said notation brings time into architecture; it is at once highly specific and ambiguous, opening possibility for discussion. We are interested in the expanded potential of notation as a collaborative instrument. When we talk about material abstraction initiated through globalization do you think notation could be used to extract honesty and unravel opacity? How does notation initiate action?

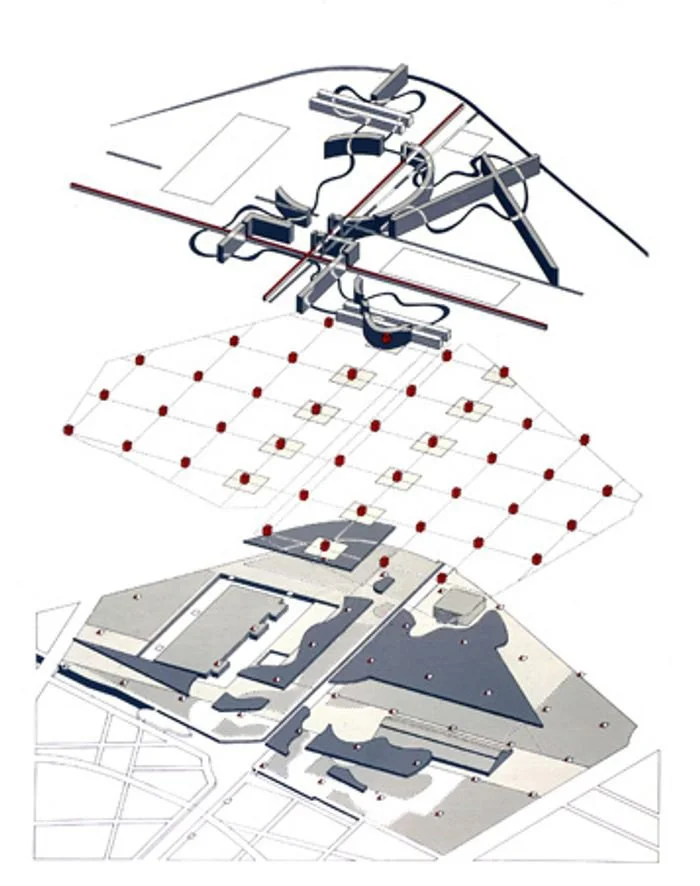

SA: If we go back to Koolhaas who came to architecture from screenwriting, he had a filmic sense of the city. For Koolhaas, the city is something dynamic, not something static at all. I think the 1983 La Villette competition is significant. The 1st and 2nd prizes went to Tschumi and Koolhaas respectively. Both had a highly diagrammatic approach. Tschumi with points, lines and surfaces and OMA with a strategy of bands. Both were very diagrammatic, notation-based strategies. They both reflect a movement away from the idea of the master plan as a kind of static, fixed endpoint for the city, and toward the idea of a script, or score for the city: a graphic device that organizes both the configuration and the events that unfold over time. Moreover, the score allows for the participation of multiple agents. In other words, it is a framework that is at once precise and open-ended while simultaneously capable of absorbing difference and change.

RM1000: Your work and practice are deeply rooted in the city. Can you talk about your relationship to the city and how it informs your practice and work as an academic?

SA: I was educated in the late seventies, early eighties. It’s difficult for students today to imagine how important a figure Aldo Rossi was for students of my generation. At that time, questions about typology and the permanence of architectural monuments in the city were very much in the foreground. Rossi had, in fact, a very keen sensitivity to the way the city changes over time, but his focus was more on permanence and the way in which certain architectural features persist over time and adapt to changing social, programmatic and political conditions. This is bound up with his ideas of autonomy and typology. So Rossi was a very important figure for me, as he was for a number of people in my generation. From another perspective, I was just starting out in architectural school in 1978 when Delirious New York was published, which was strongly focused on urbanism, but very different from Rossi’s typological approach. So the tension between Rossi and Koolhaas marked my education. I think I’ve been triangulating ever since; and this, in turn opened up an interest in infrastructure and infrastructural urbanism. Fast forwarding quite a bit, towards the end of the nineties, I became interested in what I referred to as field conditions, which are also phenomena operating at the urban scale, but different from either Rossi or Koolhaas.

Bernard Tschumi, Axonometric, Parc de la Villette Competition, 1983.

Image © Bernard Tschumi Architects

So, my interest in the city in part has its origins in Rossi and his idea that the city is a collective phenomenon: cities are about public space, public buildings and making buildings and spaces that are legible to a broader collective. I think that idea remains a strong political imperative in architecture today. And then of course, the other decisive turn coming out of the field conditions work, was beginning to get engaged in questions of landscape and later landscape urbanism. Again, questions of notation come into play because I think one of the great contributions of landscape urbanism was to call attention to the way that the city, like landscape, changes over time. So it’s a long trajectory. From the early two-thousands and the brief collaboration with James Corner and then right up to 2010, I was engaged with large-scale urban projects and landscape urbanism, but since that time I have focused on smaller scale work. In terms of questions of the city, it begins with my own education and culminates in ideas around landscape urbanism.

RM1000: The way we move through the city changes over time; the ways we circulate through the city has evolved since the ideas and strategies of landscape urbanism have been applied.

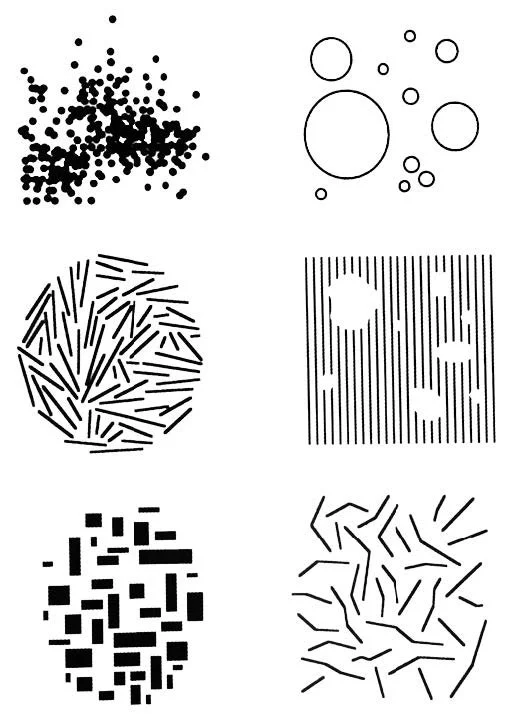

SA: It’s not accidental that I keep coming back to musical analogies. I insist that notations are time based and they also tend to be associated with collective art forms. Theater, music, performance-in a very basic way everybody in the orchestra has to interpret the score the same way. If you want to get 150 different people in the orchestra to work together to make a collective piece, they all have to follow the same score. Notations are socially based; they’re based on shared conventions, and they serve to organize collaboration. I’ll give you two more anecdotal answers from practice. During the brief period of about two to two and a half years when I was collaborating with Jim Corner, one of the things I discovered is, in a collaborative working relationship that’s only about feelings or sensibility, collaboration is never going to work. Jim and I found that if we could agree on the concepts and the diagrams that was enough to facilitate collaboration. The other anecdote is something Bernard Tschumi told me. When Tschumi won La Villette, he had never built anything remotely that large. So, he wins this competition for a major landscape park, packs it up, leaves New York, moves to Paris and does everything in his power to get this competition built. He told me over and over that he’d be in some meeting with politicians or community leaders and they’d want to introduce some change in the project—and maybe this only works in France—but he said, “all I had to do was say, look, here’s the concept: points, lines and surfaces, the points are organized in this grid, you can’t change that, you can’t move it. That’s the concept.” And they would agree. When I work with my students I tend to prefer to use the term organization as opposed to either form or program, because organization implies formal configuration, as well as the way that configuration behaves over time. A tree-like organizational system behaves one way, a networked organizational system behaves another way. The specific shape of the tree doesn’t matter. There is an organizational logic to a tree or a branch system. These are diagrammatic notation conditions that serve to organize thinking at a very abstract scale; they create a common ground for discussion and collaboration.

RM1000: You mentioned diagrammatic configurations of a tree or network; maybe that’s a good segue into the next question we have for you, which is about technology and how the technologies we use to make architecture, and those beyond it, influence form and programmatic configuration. You write in your book, Practice, that in early modernism, technology was largely reflected in symbolic form. The high-tech movement of Rogers and Piano was more literal—the building was a technology; a site where technology was invented and integrated. Do you think social, responsive, network technologies and digital mobility are influencing architecture now?

SA: No doubt. I see it happening at two different levels. One is that with the ubiquity of digital technology there is an accelerated culture of the image, a kind of spectacular organization of everything; a reduction of everything into an image. Architecture is big, expensive, and slow. In many ways, it’s exactly the opposite of media. I tend to think that architecture can still perform the role of a stable framework within the rapid social change taking place. There are plenty of people out there who disagree with me. There are people who say, why don’t we make architecture lighter, faster, quicker, and more changeable? The other aspect has been-and this is more complicated—a certain democratization of access to knowledge and expertise—a flattening of the pyramid so to speak. The peaks may not be as high, but there’s a very, very broad base. In the early modern period, the question was about gaining access to information. Today, the problem is no longer lack of access to information, but rather an excess of information; within that vast range of available information, how do we determine what information actually matters. That’s a very different challenge. I think Architecture’s role is to organize spaces of knowledge and gathering that facilitate the exchange of meaningful information and innovative ideas.

RM1000: Can you talk about technological and metabolic speed within current narratives of sustainability? As you said, architecture is slow, coming together over years. Nature is slow, ecological processes are slow. Technology and capital are fast, almost instantaneous. How do we reconcile such dramatic differences in speed?

Field Conditions Diagrams, Stan Allen, Points + Lines: Diagrams & Projects for the City, 1985. Image courtesy of Stan Allen Architect.