Let them Eat Obelisks:

The “Famine Follies” of Ireland

Roxanne Smith

In the field of architecture, the Folly has always been “useless,” the roots of its name in the French words for “madness” and “delight.” Intended solely as pictur esque decoration on estate land, they have no real program as buildings beyond serving as ornament and symbols of leisure. But during famine years in Ireland, the frivolous folly appears to have collided with basic human necessity. During the Forgotten Famine (1740-1741) and the Great Hunger (1845-1852), Famine Follies emerged in Ireland, commissioned by wealthy landowners as charitable work-re lief to provide starving tenant farmers with daily wages. Several stand to this day in the Irish countryside, amongst them the Killiney Obelisk, Connolly’s Folly, the Pyramid of Dublin, the Stillorgan Obelisk, and the Wonderful Barn.1 Though these structures colloquially known as Famine Follies are local attractions, there is little scholarship on the topic. They remain a curious footnote in the history of architec ture, and a critical moment in architecture’s relationship to utility and labor.

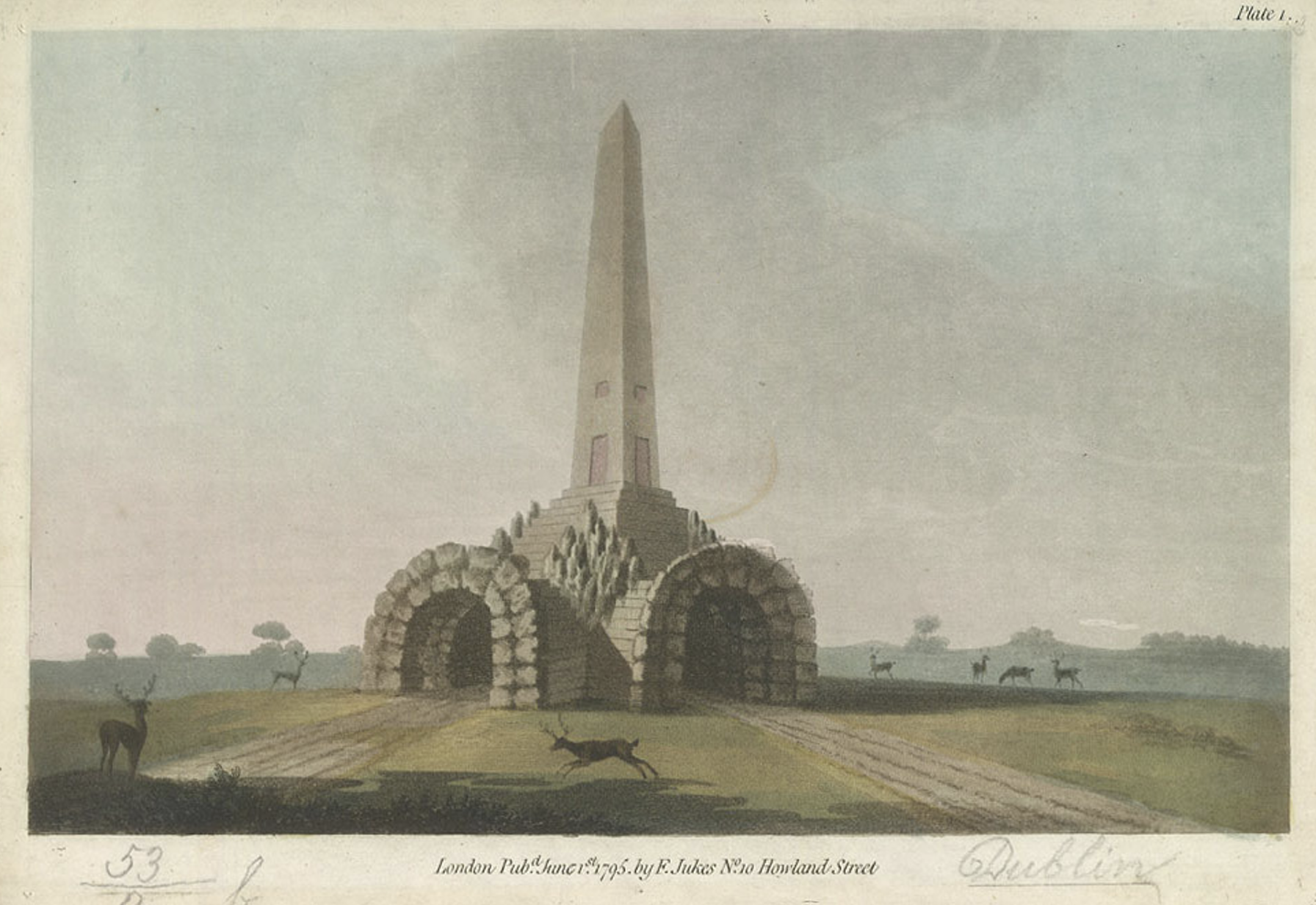

Like the relief schemes in Ireland established by the British government, charitable folly projects implied a right-wing ideological opposition to “free” aid on the part of their upper-class patrons. In the early stages of the potato famine, Parliament held an official policy against providing food to its staring subjects, instead offering aid in other ultimately ineffectual forms, including funding for infrastructure projects, resulting in untold numbers of deaths and “bridges to nowhere” across the countryside. Follies built as famine relief maintained a similarly patronizing insistence on the moral imperative of manual labor, but without the sheen of functionalism granted to infrastructure projects. If at all, the true socio-economic agenda of the Famine Follies were cloaked in abstract and rambling programs. The massive cross-vaulted Stillorgan Obelisk was a “monument to patience” in honor of the owner’s wife,2 and the Pyramid of Dublin, a meticulously-ordered stepped platform, was intended to provide scenic views of the Irish Sea, its site already a cliff towering above the coast.

The perverseness of these buildings’ conception was mirrored in the form of the folly itself. Conolly’s Folly, for instance, a butressed neo-Palladian obelisk, typified the pseudo-classical ideals of much garden architecture of the period.4 Built in the middle of a field, Conolly’s Folly towers over 140 feet, with a triple-vaulted archway supporting a central obelisk decorated with stone-carved pineapples and eagles. As a form predicated on the aestheticization of private land, the folly is ut terly mystifying as a strategy for coping with natural disasters. Follies represent ed ideals of landscape design incongruous with the reality endured by peasant farmers on Irish soil: “In many places the wretched people were seated on the fences of their decaying gardens,” wrote a priest in 1846, “wringing their hands and wailing bitterly the destruction that had left them foodless.”

The Famine Folly is, by its very definition, paradoxical—a cutesy landscape adornment entirely at odds with the dire conditions under which it was built. In one sense, follies represent the moral acrobatics of a ruling class compelled to relieve the destitution of the poor caused by both nature and man—a paternalistic redistribution of wealth through forced labor. On the other hand, they are an architecture of frictionless pursuit of leisure and the sublime. An architectural project in need of a purpose, a social purpose in need of a project.

Depending your material position, Famine Follies spiral the gamut of human experience—from pleasure to abjection, and everything in between. They are very real monuments, if accidental ones, to the lives of the millions of Irish who died during the famines, the laborers who built them, and the patrons who commissioned them. Both parties were desperate for a way to survive the famine, in life or in leisure.