Failure Mode

A conversation with Dr. Jane Cook & Collin of RM1000

Dr. Jane Cook, formerly the chief scientist at the Corning Museum of Glass, has over 25 years experience as a materials engineer. In her artwork, she employs a resourceful approach, using what’s at hand. The following text collages excerpts from conversations with Jane that took place over the last few months. These conversations offer a scientific explanation of what glass is and how it behaves. Our dialogue touches on themes of chemistry, materiality and clarity while considering the potential for failure to be productive for designers and makers.

Rm1000: I’m interested in talking about how glass breaks– how it acts as a material and how it comes undone, one weak spot at a time.

JC: How materials behave at “the human scale”–the size that we can handle and interact with, build with or relate to body to-mass– is a direct consequence of how the material is put together at sizes much smaller–down to the nature of the bonding between the individual atoms. At that scale, glass (we’ll just center this around glass in the “soda-lime” family, like windows and bottles) can be considered as an irregularly interconnected 3D network of tetrahedral nodes, with a silicon atom in the center of the node, and four oxygen atoms arranged around it reaching, branching out toward other such nodes. Many of those oxygen branches connect directly to other silicon atoms–we say they are “bridging oxygens,” shared by two silicon atoms in separate nodes. Some are “non-bridging,” connecting instead to one of the other kinds of atoms in the glass that like to bond to oxygen: such as sodium or calcium (the “soda” and “lime” of the glass name).

The bridging bonds–silicon-to-oxygen-to-silicon–are very strong bonds. Chemists call them “covalent,” because the atoms are literally sharing the electromagnetic energy of their own electrons to stabilize the structure of the adjacent atoms. It’s as intimate as atoms get without bonding to their own kind (like the covalent bonds of adjacent carbon atoms forming diamond.)

But the non-bridging bonds are weaker, “ionic” bonds. You can think of glass as having about 70% of its linkages as being tight grips. Like two people clasping hands to wrists. The rest of its bonds are more like a hand shake, or intertwined fingers.

The highly functional part is something that keeps the outside out, and lets some of the outside in. Lets the light in, but keeps the weather out. I mean, that’s going back to the Romans, right. That was the whole point, even before you could actually see through it, the point was to be a natural light source. And then there are lots of ways that you could parse that, have deviations from that, such as the reflective box of the 1960s, or the stained glass from the medieval period on with the introduction of color and form and line.

Those are sort of typical ways that people approach this, or to do something like Jamie Carpenter’s work, where you’re using the glass, but in combination with other materials to create gestures and to sort of define a feeling for the building. All those things are very much around success. Doing things really, really well. And that’s very true. But a big part of my thinking, in the last of the last two years really has been around: what else can glass do?

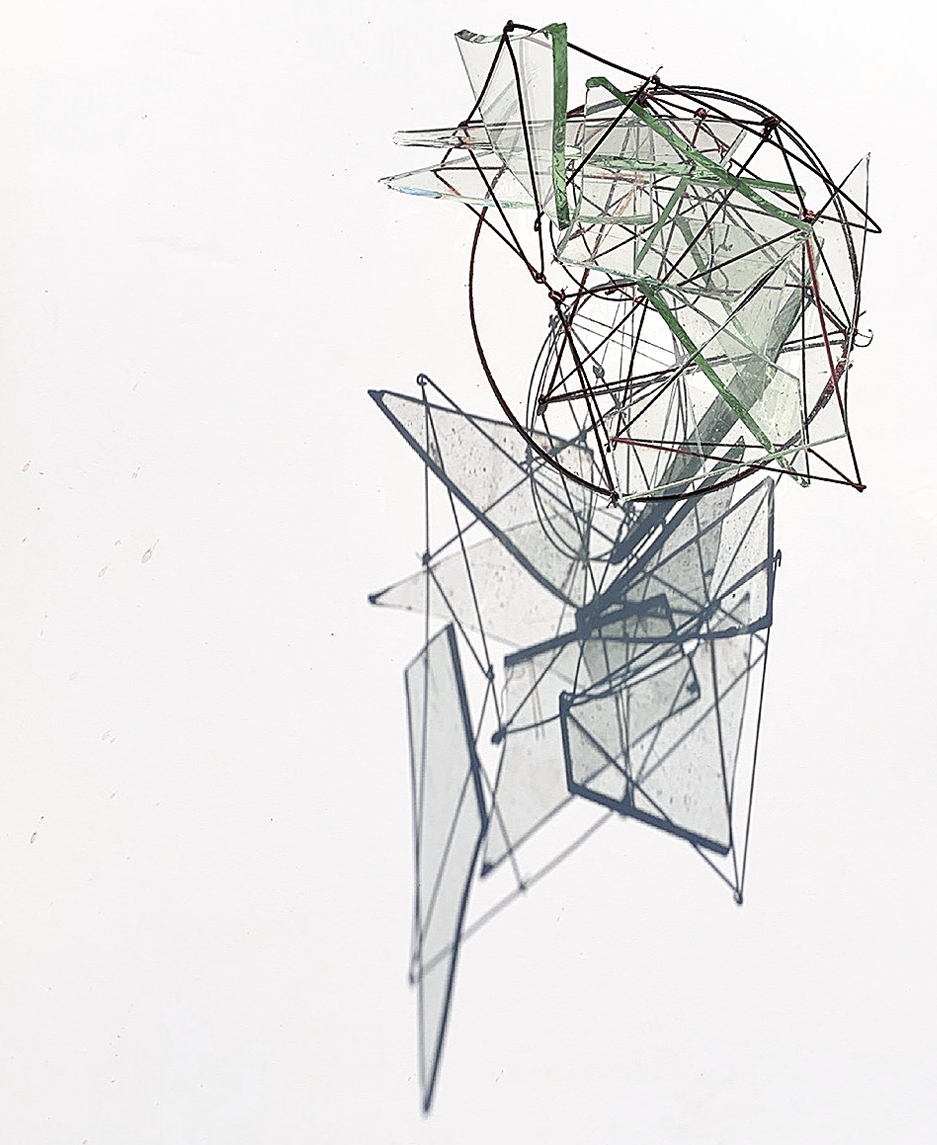

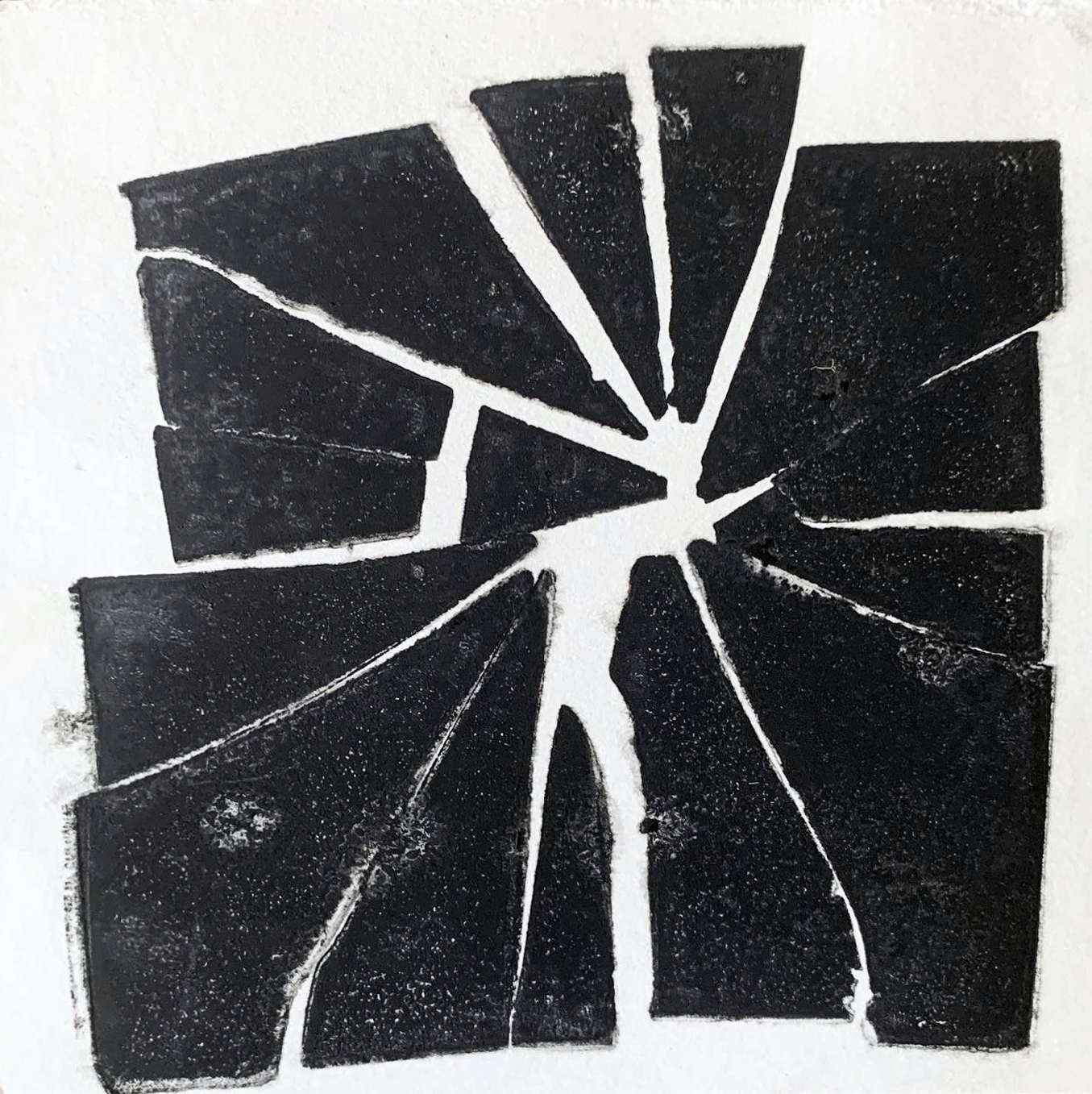

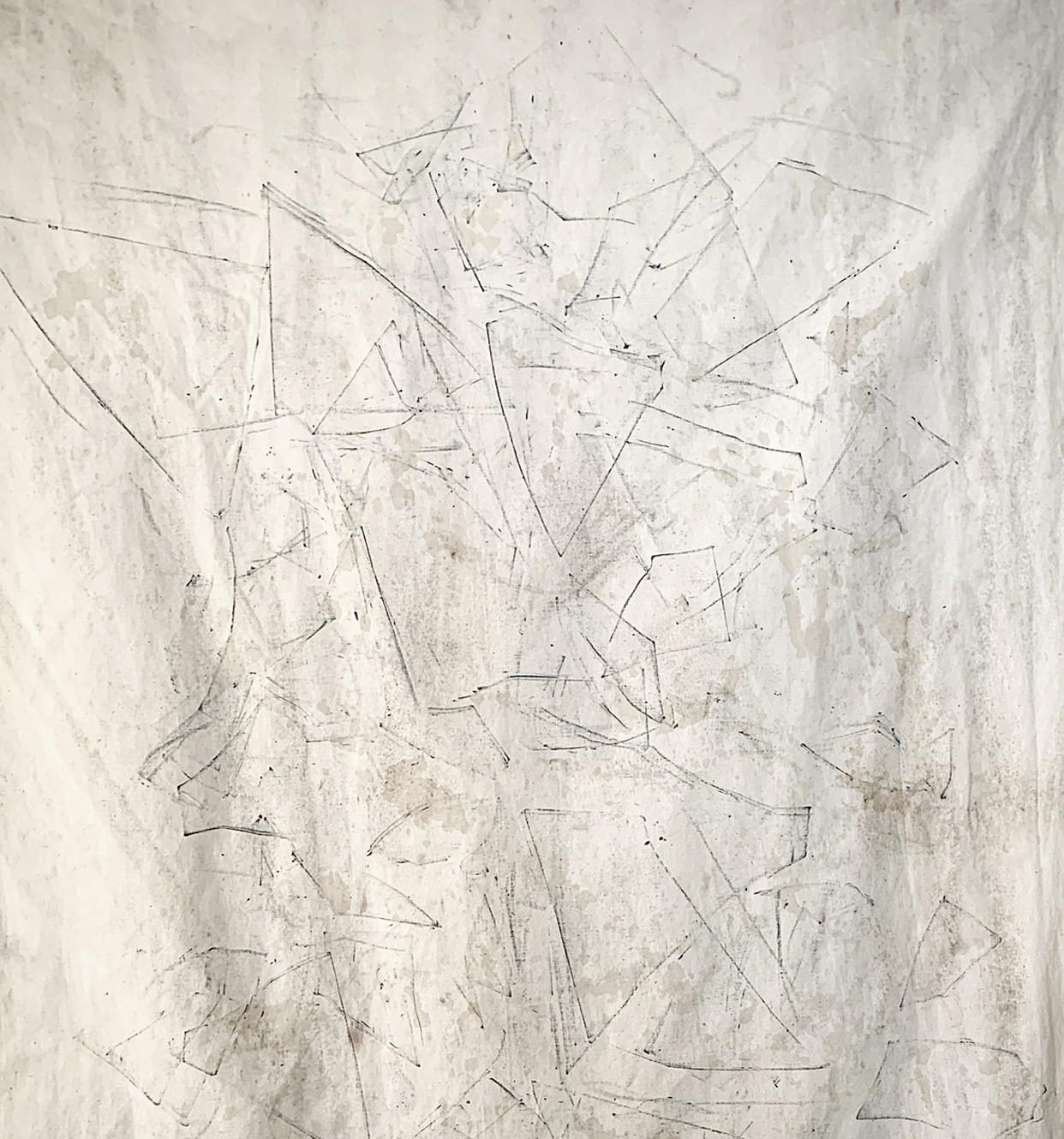

So I started by just looking at the way the different materials fail and turning that into a positive instead of a negative, right? A very sort of post-Anthropocene post-zombie apocalypse type of way of making art. What have we got around? Well, I’ve got some rust, and I’ve got an old ballpoint pen. And I’ve got an old dish towel, what can I do with that? That’s been really motivating me alongside the broken glass. So really the big theme has been turning failure into notions of success.

“.. glass has the peculiar feature amongst common materials that between the macroscale and the picoscale there are no obvious weaknesses. No grains. No soft spots. Not plasticity. Once it starts, the breaking continues until the energy is released.”

All of this is at a scale that is hard to understand if you’re not immersed in its study. It is submicroscopic, the “picoscale,” one less than the buzzword “nanoscale.” But this is the scale at which breaking happens. Fundamentally, when anything breaks, chemistry has happened. There had to have been a chemical reaction: an atom (or sextillions of them, really, when you smash a window…) all need to respond to a real change in their environment–the sudden presence of a local mechanical stress that just might be able to supply enough energy, through momentum and leverage, to overcome the strength of the bond that is holding one atom to another atom. Chemistry can be accomplished by the application of any force: chemical, thermal, electrical, mechanical.

Now, there is a hierarchy of scales of structures that can occur in materials. For example, there can be grains of different minerals in natural stone or a brick, or aggregate in cement, or the less obvious fine grains of metal within an alloy. These can be viewed with a microscope or a hand lens or the naked eye–microns to millimeters to centimeters. And when you break a rock or a pot, or when an aluminum strut fails, careful examination shows clearly that the break occurred via a combination of cracks running through the grains between the grains. The grain-grain linkages are natural weak points–disordered and poorly aligned– that makes them “weak links.” These weak spots can actually stop a crack by absorbing enough energy that things just stop, maybe short of catastrophic disintegration, or diverting the break into just a few large shards, like a dropped terracotta pot.

But glass has the peculiar feature amongst common materials that between the macroscale and the picoscale there are no obvious weaknesses. No grains. No soft spots. Not plasticity. Once it starts, the breaking continues until the energy is released.

It’s been fun for me, because yeah, I consider myself an emerging artist, even though I’ve been doing it for a long time, but I haven’t been doing it with the level of self understanding and intentionality that I’ve been able to do in the last five years or so. I know that I’m sort of beating myself up a little bit, right? Because the currency of my former life as a research scientist was: is this an invention? Is this novel? And is this useful? And as an artist, novelty and utility are not the currency, right? It’s not about being the first person to use ballpoint pen ink in this way.

So I got rust prints, people have been doing rust prints forever. But it’s fun. The novelty is personal, right? And if I’m really thinking about who I am, in an original way, and if I admit to myself as being a unique and valuable person, then the statements I make, through craft and through materiality, are inherently as valuable as I am valuable as a person.

Rm1000: When we consider the patterning or figuration of a broken window, how does the glass make decisions about how the crack will travel? Is it a condition solely of the input force, or does the glass reveal something about its makeup, or imperfections?

JC: When thinking through what happens during breakage, it’s necessary to put yourself in extreme slow-motion mode, and “be the glass,” as it were. The response to a stress is so much more than the critical flaw initiating the final state of catastrophic deconstruction. As you postulate, a variety of responses from the glass–based on its as-made condition and on what it is becoming during the response–add up to the total experience.

For example, a 1-meter square pane of glass might have a critical flaw on one of its edges (maybe a scratch from rough handling). When a sudden stress is applied by a blunt object (hit by a baseball, say) the whole sheet will flex first as a single membrane. That initial flex might bend the edge and put the f law in tension, and the crack will begin to run. Meanwhile the rest of the pane is now in motion, reverberating from the impact. As the edge of the glass lets go, all the motions of the rest of glass change since the glass is no longer held ridged in the frame, and more and more of the glass sees sudden changes in tension or compression, which then activate more f laws and more create more cracks and more ways of moving, and so on.

Eventually from a single impact and single critical break you have revealed things about aspects of the entire pane, including not only manufacturing and handling/installation flaws, but how the glass was mounted, how far off the ground it was, etc. It’s the story of not just what was there, but what happened– quickly to our eye, but methodically on the timescale of the breakage.

Is all the work about being broken? Is it? Are you attached to the language of brokenness? What does that mean psychologically, personally? Or as a reaction to the world? I often get into discussions about being queer and trans and whether this is somehow an expression of that. Especially younger people just coming out, are really beginning to imbue all of their artwork with their queerness. And they asked me, “Do you feel that way too?” And, and I say “Not really, I’ve had a different journey than you.”

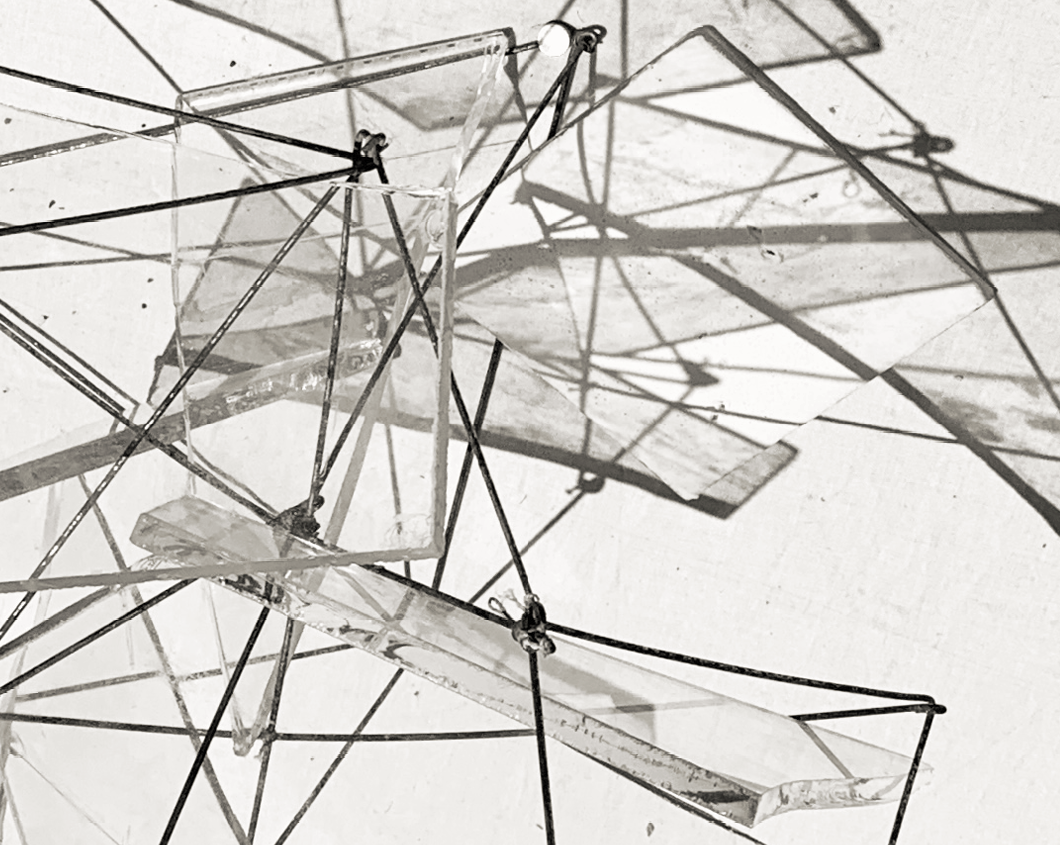

I think we don’t do enough to educate people, generally, about the failure modes present in the made world and how they should be reflected in our personal risk management calculations. In my own artwork during the pandemic, I’ve been exploring deeply the aesthetic and conceptual utility in failure modes, with things like pulling prints from glass shards and rusted iron, or recently exploring what is conveyed by sundials made with gnomons made from broken glass.

Rm1000: And finally a new thought to introduce to the conversation: clarity. In our daily life, the role of the glass is often to be an “invisible” boundary layer. We don’t really encounter the materiality of glass until it has broken or failed. There is an intensity with which we will glass to be this optically perfect entity that disappears from our surroundings making it that much more devastating or upsetting when it’s broken. What I’m trying to get at is that transparency often feels in opposition to the term, materiality, as though transparency is more akin to immateriality. I think there is an opportunity to challenge this notion and I wonder if you have thoughts on this.

JC: I would say some of the work that I’m most proud of that I, unfortunately, talk the least about, have to do with making the glass in our screens, the ones that you’re looking at right now and in your cell phones. Not the gorilla glass on the outside, but the glass actually on the inside with a liquid crystal display. The level of purity, homogeneity, flatness and smoothness of those surfaces is almost pathological. The things that have to be done in a machine system in order to have glass like that come out the other side have strained the limits of machine and control technology. It’s been a progressive thing that’s gone on over centuries really.

Once you see that this stuff can actually be clear, however slightly yellowish or slightly greenish. We figured out the ingredients to make it water white: a pinch of manganese or a little bit of antimony or something like that. Then you can decolorize it completely, then you’re making clear glass.

But it becomes an interesting example of this idea that when you have something that’s very, very clear, it is easier to distinguish flaws. The more transparent and perfect the glass is, the more impurities stand out and greater is the potential for disruption.

The question of glass clarity is a good one. In so much of what we ask glass to do, its success is measured in part by our not noticing it. That sense of connection to its functionality, to keep things isolated in one way but connected in others (windows, computer displays, soda bottles, etc.), and the shock when the barrier is breached is profound. I’ve seen it manifested in interactions with the public complaining to me about iPhone screens and “Pyrex” cookware, and from artists confused about annealing schedules, color compatibility, and mixed media work.