The Form Of Value

TEN Studio

Chapter 1: The Form of Value

Value is the outcome of design effort when it is open, highly collaborative, and purpose-driven. It then surpasses the refinement of a particular aesthetic to cultivate an aesthetic of discovery.

Today, designers assume need is relative, and the metrics of its fitness are self-determined. Imagination for the creative calibration of capital, labor, law, and material fact appears sidelined in favor of the formalization of aesthetic prejudice. This may still reflect enduring principles of the modern movement, which prioritized aesthetically impenetrable forms through highly codified design processes—without considering that while design actions shape reality, they are also shaped by evolving dynamics.

The twentieth century arguably established the designer as a new type of creative agent, tasked with materializing coherent, stylistic architectural commodities for the betterment of society. While this approach brought high cultural visibility, a decipherable formal language, and alignment with the emerging values of new social structures, it also fetishized aesthetic closure and the production of simplified, prescriptive solutions. Design completion became synonymous with finality, creating an irresolvable distance between the object, its use, and the material world.

While the plurality of contemporary design output has enabled a vast diversity of speculative production and expression, it can be argued that architectural practice still follows an uncritical modern habitus. Design often focuses on refinement and is viewed primarily as a linear, iterative effort to charge an object with distinction, frequently neglecting the complexity of human and environmental interactions. The core issue lies not in the belief in the latent potential of design agency, but in the inertia of transforming entrenched understandings of how the value of design is conceived, taught, and applied.

Although the acknowledged limitations of the modern movement ignited calls to abandon aesthetic unity, an alternative interpretation of its founding tenets may reveal parallels with contemporary efforts to reestablish design purpose. Central to the modern idea of total design was the belief in a conscious, cooperative effort across all creative disciplines in the act of architecture. This positioned the architect as a creative facilitator who would actively integrate various artistic knowledge through new models of collaborative design. By breaking with the romantic tradition of the singular, inspired artist, the new architect designed through what might be called collective design intelligence—leveraging parallel domains of creative knowledge into a coordinated system of production. This suggests that the failure of the modern movement lies not in its ambition for aesthetic unity but in its limited appreciation for the radical potential to redesign the design process itself.

“Design, at its core, is an intentional practice.”

Design, at its core, is an intentional practice. It lends specific form to novel solutions and is judged by its performance and appeal. Given the increasing complexity of designing the built environment today, the act of design requires knowledge beyond what is typically cultivated in creative disciplines alone. Designing today means suspending assumptions and initiating an exploratory process from zero knowledge. It involves open research, dialogue, analysis, prototyping, and testing from many perspectives. Rather than remaining entrenched in normative processes and vainly seeking contemporary expression, design can be reimagined as a reflexive, critical, and creative act—open to the shared pleasure of the unexpected. This design process can be understood as a fundamental act with the potential to respond more effectively to unique spatial needs and the specific natures and circumstances of users.

To design something is to stake a core idea capable of guiding shared experience around it—an acknowledgment that every act of making defines and manages tolerance. The margins of this tolerance, if tested from many perspectives, serve to delimit a consensual space for experimentation and invention. Design effort is nothing more than an exposition of this tolerance. Such acts of creative collaboration have the potential to integrate unique domains of knowledge and, by building common ground, weaken ideological extremes. By embracing its inventive nature from first principles, design can demonstrate its intersubjective value and offer a form of cultural immunity to obsolescence

Chapter 2: House of 5 Women

Situated in the agricultural landscape near Gradačac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the House for Five Women is a shared home for women disadvantaged by social injustice, war, or violence.

More than a physical structure, it represents a paradigm for an evolving framework of engagement and adaptability. It is a place for reestablishing trust, discovering care, and building relationships. Residents live independently, together. The house nurtures both a culture rooted in the identity of its environment and the redefinition of this identity in the everyday.

The story begins with Hazima Smajlović, a woman born in Bosnia who fled to Switzerland during the wars of the 1990s, where she is currently based. She has spent her life building networks and formats of care and support for women in Bosnia. After inheriting a plot of land in the agricultural area surrounding Gradačac, she formulated the idea of supporting socially disadvantaged women and approached Engineers Without Borders and TEN. Inspired by a seven-year collaboration with Engineers Without Borders Switzerland, TEN, the NGO Vive Žene, the Gradačac municipality, and people of good will, resources were collected and secured over time through hundreds of donations. The project team governed these resources transparently through yearly reports and collective decision-making. In this way, project ownership is shared, and the design purpose becomes tangible.

Working closely with TEN, landscape architect Daniel Ganz harmonized the building with its surroundings, incorporating trees and elements from the local environment while developing ground surfaces and a garden layout. Artist Shirana Shahbazi enhanced the structure with color, transforming the facade into a dynamic tapestry-like surface that continuously shifts in appearance. The panel colors and patterns were tested both on site and at a nearby car paint workshop, where routine vehicle repair took on an artistic dimension. The facade design gives the house an unexpected, nonresidential character within its context, offering a strong and welcoming presence for all.

“The surfaces are rough, unapologetic, not precious, resilient, generous, and open for potential; exactly what architecture dealing with radical rethinking of comfort is about.”

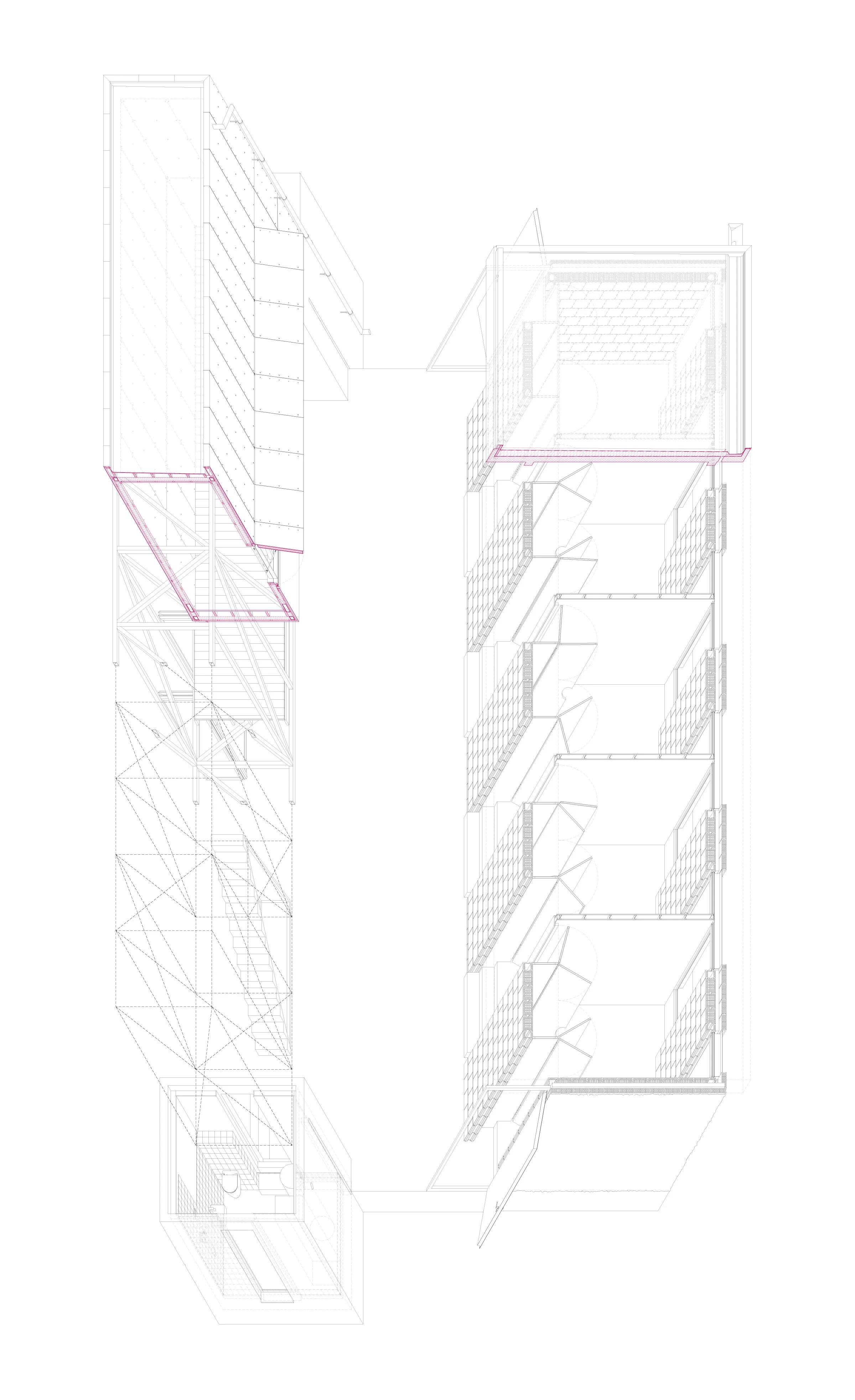

The house is based on the idea that people grow both individually and together. The layout supports privacy as well as shared experiences. The five private rooms are two steps up from the common living space, all equal in size and orientation, and equipped with cabinetry and kitchenettes. Ten double doors along the main facade turn typical room access into a model of an interior street. When opened together, they create a twenty-five meter-long threshold that connects the interior with the landscape and advocates openness and a connection to the land.

At approximately eighty square meters, the living area is larger than what one could typically operate or afford alone. It expands on the traditional south-oriented porch typology. In summer, it provides shade and creates spatial depth. This everyday room—situated between inside and outside—becomes a kind of field room for food processing and social encounters. It opens on three sides and includes a skylight that visually separates shared from private zones. The expansive communal space functions as a kitchen, welcome zone, workspace, and living room—necessitating interaction and mutual support.

Above it, suspended between two utility rooms, lies a twenty-five meter-long multifunctional space inspired by the traditional typology of pastoral storage. Built as a space truss and clad in colored metal panels on the outside and timber on the inside, this structure is both outspoken and introspective as needed. This “joker room” accommodates seasonal activities, from food storage to hosting additional residents. Its design ensures that the house remains adaptable to changing needs. It opens only through a series of movable panels facing north. The utility rooms, cast in concrete, feature restrooms with small doors connecting directly to the landscape for gardening access.

The women—whose length of stay is determined solely by their own choice—are encouraged to cultivate the adjoining agricultural plot, conceived as a productive space supporting independence. The completion of the house does not mark the end of the project but the beginning of its cohabitation. The project team remains actively involved through the NGO Naš Izvor, responsible for the building’s maintenance and evolution, ensuring it continues to adapt to its residents’ needs and stands as a testament to the principles of collective design effort.